Like most Gothics, the Australian Gothic has acquired its own distinct aesthetic—most frequently, an abject unpleasantness and atmosphere of sand-scoured horror. Personally, I’d like to blame both Evil Angels (aka A Cry in the Dark) and Gary Crew’s memorably effective Strange Objects (1990) for many of my own nightmares.

It is also, like most Gothics, tangled up with the genre’s own past, and inextricably knotted into colonial and imperial histories as well as the multitude of other mirrored and recurring histories typical of a Gothic plot. And Australia has a bloody history, with terrible things done and still being done. Yet there are also stories which, without shying away from terrors (although not necessarily innately any better at handling the true history than other varieties of Australian Gothic), manage in a variety of fascinating ways to capture a sense of great (even sublime, often terrifying, never false) beauty.

Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay (1967)

This slim, daylit, gripping novel continuously flirts with mystery (it begins, after all, with the disappearances of several girls and their teacher at a boarding school’s St Valentine’s Day picnic). Yet the book is never about what happened, whether that day or in the past. If it is about anything, it is about the price of a failure to move forward, and the frightening but admirable necessity of dissolution into an overwhelming and impersonal beauty. Few adaptations of or responses to the book capture this element (although the points of difference are illuminating). Peter Weir’s 1975 movie comes closest, even filming at times through bridal veils to capture the explicitly painterly effect of the novel. But even that faithfulness (consider the lizard which, in the novel, “emerged from a crack to lie without fear in the hollow of Marion’s arm”, and which lingers by the sleeping Miranda in the movie) trades the rippling shimmer of the novel for an (effective!) eerie somnolence—almost as if the instantaneous experience of a painting had been drawn out into the length of a script.

Even Lindsay saw the novel more as an artwork than a novel (she was an artist herself, her husband was head of the National Gallery of Victoria, and her brothers-in-law were influential artists—the film Sirens is about one of them). Even the title of the book is that of a painting. But the book is never weighed down by its visuals. Ultimately, for all the deaths and casual betrayals and great absences, and the sense of something vast and humming and alien under the surface of the world, Picnic at Hanging Rock is consciously and explicitly a Gothic novel that takes place almost entirely in daylight, and in which “Everything if only you could see it clearly enough, is beautiful and complete…”

The Dressmaker by Rosalie Ham (2000)

There is no shame in encountering this novel first in the 2015 film, starring Kate Winslet. It’s a delight, with all the textures of quality cloth, and the chalky light of a Tom Roberts painting. (I’ve described it to a few people as Chocolat crossed with this one Barossa Valley tourism ad, but make it fashion). The novel, squarely Australian Gothic and with a slightly harder edge, is equally stunning. For while while Picnic at Hanging Rock takes place in the tidal churn where English gardens break themselves against the inexorable presence of Mount Diogenes in the months before Australia’s federation, The Dressmaker is set in cropping country in the 1950s, hardscrabble and dust-gilded. And into its structure is set and pleated the weight and roughness and silk of fabrics.

It’s a novel of a woman’s return, in the full power of hard-earned professional skills, to overset the ingrown relationships of a small town from which she was exiled as a child. That she does it through fashion is never sentimental—it’s ferocious and scathing, stiffened and knife-edged. There are aching secrets, true losses and undeserved deaths there, too, and with them the same incidental benevolent glimpses of the supernatural (never threatening, never explained, used only to finish the story of a loving sorrow), the same lingering fairy-tale horror that seeps into Picnic at Hanging Rock. And with all this comes the same affection for real beauty—not the looming presence of the rock, but the human-scale power of objects and clothing and gardens and fire, from the first glimpse of the town, a “dark blot shimmering at the edge” of “wheat-yellow plains”, to the last disappearance of “very effective baroque costumes”. Further, each section opens with a definition of a fabric, an appreciation of its tactile properties and proper purposes: “a durable fabric if treated appropriately”, “irregular wild silk yarn…. crisp to handle and with a soft lustre”, “a striking texture on a dull background”. For while in this story beauty may be used to clothe awfulness, it never disguises it, and neither the fact of that beauty nor the terrible promise of it is never called into question by the novel.

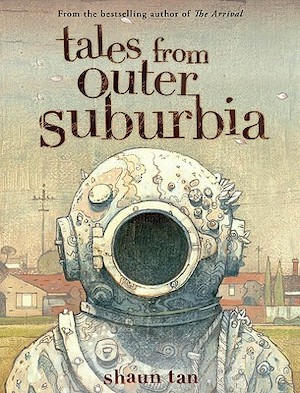

Tales From Outer Suburbia by Shaun Tan (2008)

Shaun Tan is far from under-recognised as an illustrator (most recently winning the Kate Greenaway award for Tales from the Inner City—the first BAME author to do so). However he is viewed primarily as an illustrator and artist, and the books he writes—being heavily illustrated—are frequently labelled as children’s books. But he has always been a writer and teller of speculative fiction, and the Kate Greenaway-award-winning book would be better categorised as a collection of masterfully cool—and occasionally achingly bleak strange speculative fiction, half glimmering post-apocalyptic dreamscape, half longing, urban-weird folk-horror.

But the preceding collection, Tales from Outer Suburbia, is a warm, effusively illustrated collection of deeply affectionate—if extremely unexplained—tales, and a number of the stories in it are either squarely Australian Gothic or increase in fascination if you read them that way. These include a family scrabbling to survive in a hostile Australian landscape who discover a secret hidden in the walls of their house—and what the neighbours might know about it (“No Other Country”), children in a magpie-stalked suburb encountering a forbidding neighbour and the ghost of a pearl diver (“Broken Toys”), a distinctly Australian urban development haunted by the presence of inscrutable terrors watching through the windows (“Stick Figures”), judgements passed and witnessed by a court of the voiceless (“Wake”), and the fearsome inexplicable loveliness of nameless night-time festivals (“The Nameless Holiday”), and how people in a landscape of backyards and watching neighbours choose to live when in the immediate shadow of a potential apocalypse (“Alert but not alarmed”).

The Australian-ness is clearly identified in the layered, textured, bounding artwork; the doublings and secrets and hauntings are indisputably Gothic. But they are beautiful, all these stories: painterly and allusive, deceptively slight and enormously resonant, bird-filled, haunted by the possibility of joy, the ghost of understanding. (I recommend writers spend a little time studying what Tan does in his illustrations—the exuberant and ominous textures, the references and hints and possibilities and all the narrative techniques that appear in the art, let alone the accompanying prose). While Tales from Outer Suburbia is littered with silvery flecks of loss, there’s a warm, impossible, grand (sometimes terrifying) beauty at the core of (or wilfully and relentlessly ornamenting) what could in other hands be merely grim.

Taboo by Kim Scott (2017)

There are reasons not to apply the label Australian Gothic too broadly or uncritically (see note at the end of this article). However, Kim Scott does consider his novel to include “a touch of Gothic”, and it is Australian, so if you are interested in Australian Gothic, its possibilities and its context—and particularly the histories the subgenre often evade—Taboo is an important book.

The novel follows the return of the extended Coolman family (of the Noongar people) to Kokanarup (the site of a nineteenth-century massacre) for the opening of a Peace Park. Certainly there are terrible things happening in this novel’s present as well as its past: violence and abuse and injustice, murder and incarceration and more. But the European horror of the Australian landscape is (naturally!) absent. The physical world of Taboo is luminous and present, ethereal and earthy, wild and polished by generations of hands—past and present and not quite either, beloved of and lovely to those who know it well and those who are discovering it for the first time. From the wildly strange opening scene—from a perspective curiously disconnected from linear time, the reader encounters a town as a truck careens through it, cascading whispering wheat from which an impossible figure slowly rises—through convoluted cruelties and bloodlines, and back to an understanding of that first moment of uncanny enchantment, the world of this novel is gilded.

Day Boy by Trent Jamieson (2015)

Day Boy is a little different from some of the other books I’ve mentioned here. For one thing, it’s a post-apocalyptic vampire novel, the story of a vampire’s young daylight servant who is growing out of childhood, and whose loyalties and choices for the future in a slowly decaying world will be tested. But while it is set in a small Australian town around which the bush presses, and while it deals with death and teeth and eternity, the tone is remarkably tender, and as the world crumbles the book begins to feel like a certain type of rural coming-of-age novel told backwards. I read it immediately after reading Willa Cather’s My Antonia, and there were such odd resonances there! In the Australian context, it has some of the bleak gentleness of one of James Aldridge’s St Helens stories—The True Story of Spit Macphee, perhaps—or a Colin Thiele novel (Storm Boy or The Sun on the Stubble). And yes, it is about vampires and death and the slow end of the world, but alongside the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of the modern world, there is an appreciation of the enduring, small kindnesses and daily joys of life.

Glitch (2015-2019)

There is also some fabulous Australian Gothic television being released lately. Often it segues into Australian Noir. A particularly notable treatment of the genre, though, has been season 1 of Glitch. This is a show not unlike The Returned in its initial set-up of impossible returns and deaths apparently reversed (or suspended), although it steers its own course from there. However it is also worth watching for its remarkable attention to and faith in surfaces keenly observed and beautifully depicted: faces that instantly evoke an era, the wind moving over whispering blonde grass, the affectionate inclusion of just the right mugs in a certain type of kitchen—terrible things happen, dreadful mysteries lurk, but beautifully, in a world worth staying in.

***

“Australian Gothic” can be a fraught term, particularly if applied incautiously to works by Indigenous authors. At the same time, the representation of Australian history (or lack of it) in many explicitly Australian Gothic books is problematic (and I can’t exclude myself here: the failure—and perhaps inability—of the folk of Inglewell to confront their histories leads to many of the problems of Flyaway). This is not least because a core motif of the Australian Gothic has been the image of an externally-based culture (English or otherwise) grappling with existence in a landscape incompatible with its ideas, while also actively avoiding dealing with that history. There are, however, many great books by Indigenous Australian authors which should be read and appreciated by readers of the Gothic, for their own excellencies as well as for the context they provide, the stories that are omitted by other books. Just a few authors to look out for include Ellen van Neerven (Heat and Light), Ambelin Kwaymullina (Catching Teller Crow, with Ezekiel Kwaymullina), Claire G. Coleman (Terra Nullius), Melisssa Lucashenko (Too Much Lip), and Alexis Wright (Carpentaria).

Also, I don’t want to imply that histories of displacement, massacre, and worse, should be “beautified”, or that beauty—even a sublime beauty—makes a book better. There are many wonderful bleak and grim books. Rather, the stories considered here are those which I found remarkable for pushing back against the tradition of an unpleasant representation of the physical world, and making a space for a great and terrible beauty, and intriguing new contexts for the Australian Gothic.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Kathleen Jennings is a writer and illustrator in Brisbane, Australia. She was raised on fairy tales on a cattle station in Western Queensland, and practiced as a translator and a lawyer (which is all stories, isn’t it?) before returning to undertake a Master of Philosophy in Creative Writing (Australian Gothic Literature) at the University of Queensland. Her short stories have appeared on Tor.com, in Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, in anthologies from Candlewick, Ticonderoga and Fablecroft Publishing, and elsewhere. As an illustrator, she has been shortlisted for one Hugo and three World Fantasy Awards, and has won several Ditmars.